Sri Lanka

In 2009 after a 26 year long civil war, which included different failed ceasefires, the Sri Lankan military defeated the separatist group Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). Since then, the government has been dominated by the majority Sinhalese ethnic group. Many grievances of the Tamil population have not been addressed and the international community pointed towards the slow progress in establishing and implementing transitional justice measures and in strengthening human rights and security. More recently, the human rights conditions, including the respect for civil liberties have been improving, but surges of violence between Buddhist and Muslim populations in 2018 have raised the question of the quality of security and peace.

The Survey

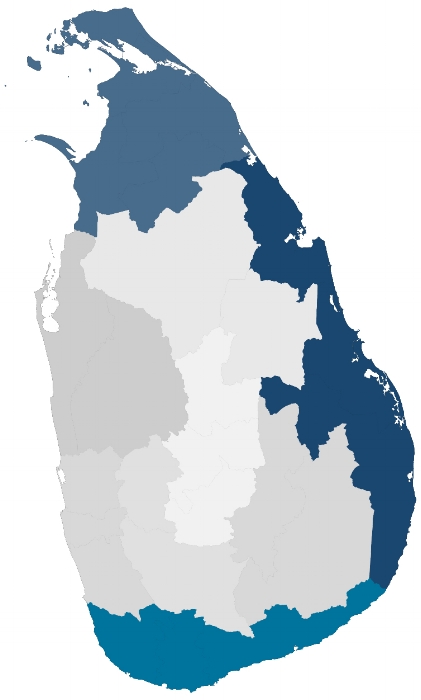

Surveyed Provinces in Sri Lanka

In August and September 2018 we carried out surveys in the Northern Province, the Eastern Province and the Southern Province (shaded blue in the map). The survey included a wide range of questions on the perceptions of security and stability, the security forces and on media consumption.

The Northern and Eastern Province were selected because these area were severely affected by the civil war. The Southern Province was chosen to contrast the experience of the other two Provinces. The three Provinces also represent very different ethnic and religious communities. The Northern Province is dominated by Sri Lankan Tamils and Hinduism, the Southern Province by Sinhalese and Buddhism, while the Eastern Province combines different ethnic groups, including Sri Lankan Tamils, Sri Lankan Moors and Sinhalese, as well as Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam.

For the survey we randomly selected 800 respondents in the Northern Province, 700 in the Eastern and 500 in the Southern Province, to be representative at the Province Level. The survey was implemented by our local partner Vanguard Survey PVT LTD.

Different aspects of peace and security

Overall our respondents were rather pessimistic about the future political stability of the country - weeks before President Sirisena sacked Prime Minister Wickremesinghe.

Perceived projected political stability by ethnicity

If we concentrate on the responses by the two major ethnic groups in the country, the Sinhalese and Sri Lankan Tamils, we see some variation. Over 70% of respondents who self-identified as Sinhalese thought the country was heading towards political instability, compared to just over half of respondents who self-identified as Sri Lankan Tamils. The remaining respondents primarily self-identified as Sri Lankan Moors; of those only about one third thought the country was heading towards political instability.

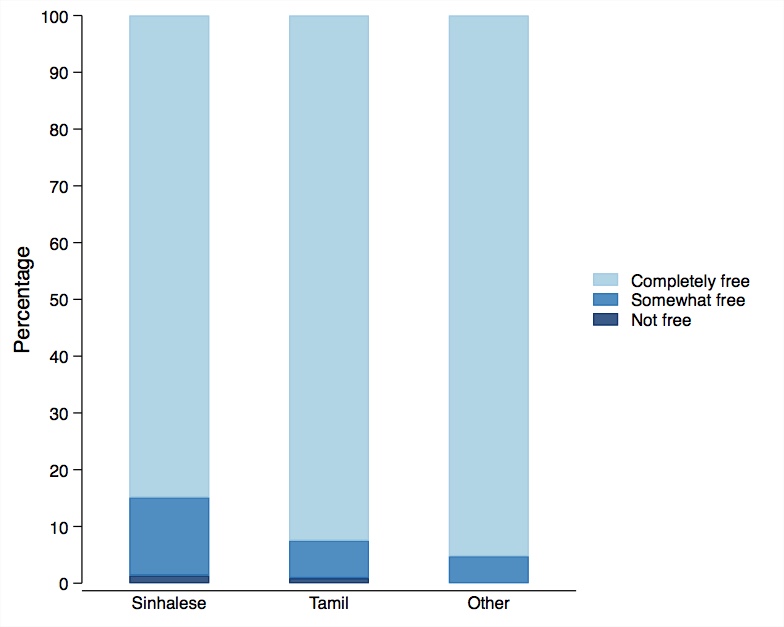

Respondents were asked to assess the quality of various political rights and civil liberties. Our results show that the vast majority of respondents, irrespective of ethnicity, feel that they can vote freely.

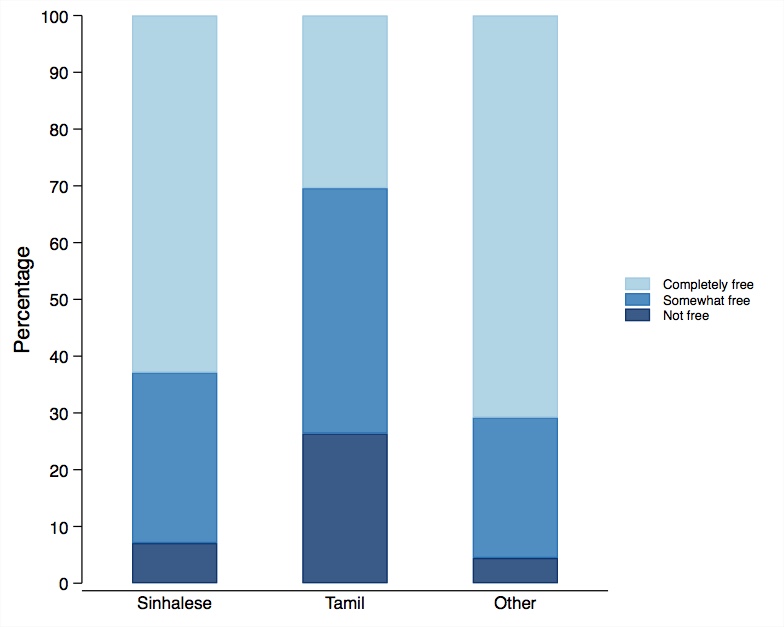

A different picture emerges when we asked the respondents how free they felt to say what they think in public. While over 60% of Sinhalese felt completely free to speak their mind in public, this applied to only one third of Sri Lankan Tamils. We received similar responses when we asked about how free they felt to join any political organisation they wanted. Feeling free to vote does not equate to feeling free to participate in the political process.

how free do you feel to choose who to vote for without feeling pressured?

How free do you feel to say what you think in public?

Armed Groups

We asked respondents whether they had encountered an armed group since the end of the civil war that was neither the police nor the military. We did not further specify the nature or name of such an armed group. Only about 7% (N=152) of our sample reported a direct encounter with an armed group since the end of the war. Almost all of these responses came from the Sri Lankan Tamil population in the Northern Province.

Next, we asked those who reported to have encountered an armed group, whether they felt rather threatened or rather protected by this group. Almost all Tamils in the Northern Province said that they felt rather protected by the armed group. This positive respond starkly contrasts the responses we received in Nepal.

Direct encounter with an armed group that was not the Sri Lankan police or military

Nature of the encounter with the armed group

Publication on Impact of a “Victor’s Peace” on Different Experiences of Peace

Using these survey data, we investigate whether the “victor’s peace”, where a civil war is terminated with a clear victory of one side over another, leads to different experiences of peace in the post-war context. Our results show that even a decade after the Sinhalese government defeated the Tamil Tigers, which claimed to represent the Tamil minority, the Sinhalese and Tamil perceive ethnic relations, freedom of speech, fairness of the government and overall security quite differently. Yet the more positive experiences of the Sinhalese majority do not translate into a more optimistic outlook for the future. For the victor, concerns about political divisions and instability have surpassed the legacy of the previous civil war. Click here for this study.